F30 Manic episode. Bipolar disorder, what is it? manic episode

Publication date August 9, 2018Updated October 25, 2019

Definition of disease. Causes of the disease

Mania, also known as manic syndrome, represents a state of abnormally increased levels of arousal, affect and energy, or "a state of increased general activation with increased affective expression along with lability (instability) of affect." Often, mania is considered a mirror image: if depression is characterized by melancholy and psychomotor retardation, then mania suggests an elevated mood, which can be euphoric or irritable. As the mania intensifies, irritability may become more pronounced and lead to violence or anxiety.

Mania is a syndrome caused by several causes. Although the vast majority of cases occur in the context of manic disorder, the syndrome is a key component of other psychiatric disorders (such as schizoaffective disorder). It can also be secondary to various common diseases (for example, multiple sclerosis). Certain medications (such as Prednisolone) or the abuse of narcotic substances (cocaine) and anabolic steroids can cause a manic state.

By intensity, mild mania (hypomania) and insane mania are distinguished, characterized by symptoms such as disorientation, psychosis, incoherent speech and catatonia (impairment of motor, volitional, speech and behavioral spheres). Standardized instruments such as the Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale and the Young Mania Rating Scale can be used to measure the severity of manic episodes.

A person with a manic syndrome does not always need medical attention, since mania and hypomania are long associated with creativity and artistic talent in people. Such people often retain sufficient self-control to function normally in society. This state is even compared with a creative upsurge. Often there is an erroneous perception of the behavior of a person with a manic syndrome: one gets the impression that he is under the influence of drugs.

If you experience similar symptoms, consult your doctor. Do not self-medicate - it is dangerous for your health!

Symptoms of manic disorder

A manic episode is defined in the Diagnostic Manual of the Psychiatric Association as "a distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, intemperate, irritable mood, and of an abnormal and sustained increase in activity or energy, lasting at least a week and for most of the day." These mood swings are not caused by drugs, medications, or a medical condition (such as hyperthyroidism). They cause obvious difficulties in work or communication, may indicate the need for hospitalization to protect themselves and others, and that the person is suffering from psychosis.

Symptoms of a manic episode include:

Although the activities that a person performs while in a manic state are not always negative, cases are much more likely when mania leads to negative consequences.

The World Health Organization classification system defines a manic episode as a temporary state in which a person's mood is higher than the situation requires, and which can range from a relaxed good mood to a barely controlled excessively high mood, accompanied by hyperactivity, tachypsia, low need for sleep, decreased attention and increased distractibility. Often the confidence and self-esteem of people with mania are exaggerated. Behavior that becomes risky, stupid, or inappropriate (perhaps as a result of the loss of normal social constraints).

Some people with manic disorder exhibit physical symptoms such as sweating and weight loss. In full-blown mania, a person with frequent manic episodes will feel that there is nothing and no one more important than himself, that the consequences of his actions will be minimal, so he does not have to restrain himself. The hypomanic connections of the individual with the outside world remain intact, although the intensity of the mood intensifies. With prolonged lack of treatment for hypomania, "pure" (classic) mania can develop, and the person goes to this stage of the disease without even realizing it.

One of the characteristic symptoms of mania (and to a lesser extent of hypomania) is the acceleration of thinking and speech (tachypsychia). As a rule, in this case, the manic person is excessively distracted by objectively unimportant stimuli. This contributes to absent-mindedness, the thoughts of a manic individual completely absorb him: a person cannot keep track of time and does not notice anything but his own stream of thoughts.

Manic states always correlate with the normal state of the suffering person. For example, a gifted person may, during the hypomanic stage, make seemingly "brilliant" decisions, be able to perform any actions and formulate thoughts at a level far exceeding his abilities. If a clinically depressed patient suddenly becomes overly energetic, buoyant, aggressive, or "happier," then such a change should be understood as a clear sign of a manic state.

Other, less obvious elements of mania include delusions (generally grandiosity or haunting, depending on whether the prevailing mood is euphoric or irritable), hypersensitivity, hypervigilance, hypersexuality, hyperreligiosity, hyperactivity and impulsivity, compulsion to over-explain (usually accompanied by speech pressure), grandiose schemes and ideas, reduced need for sleep.

Also, people suffering from mania during a manic episode may take part in dubious business transactions, waste money, engage in risky sexual activity, abuse drugs, excessive gambling, tend to reckless behavior (hyperactivity, "daredevil"), violation of social interaction (especially when meeting and communicating with strangers). Such behavior can increase conflicts in personal relationships, lead to problems at work, and increase the risk of conflicts with law enforcement. There is a high risk of impulsive behavior potentially dangerous to self and others.

Although "significantly elevated mood" sounds rather pleasant and harmless, the experience of mania is ultimately often quite unpleasant and sometimes disturbing, if not frightening, for the sick person and for those close to him: it promotes impulsive behavior, about which you may regret it later.

Mania can also often be complicated by the patient's lack of judgment and understanding regarding periods of exacerbation of characteristic conditions. Manic patients are often obsessive, impulsive, irritable, belligerent, and in most cases deny that anything is wrong with them. The flow of thoughts and misperceptions lead to frustration and reduced ability to communicate with others.

The pathogenesis of manic disorder

Various triggers of manic disorder are associated with the transition from depressive states. One common trigger for mania is antidepressant medication. Dopaminergic drugs such as dopamine reuptake inhibitors and agonists may also increase the risk of hypomania.

Lifestyle triggers include irregular wake/sleep schedules and lack of sleep, as well as extremely emotional or stressful stimuli.

Also, mania can be associated with strokes, especially brain lesions in the right hemisphere.

Deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus has been associated with mania, especially with electrodes placed in the ventromedial STN. The proposed mechanism suggests an increase in excitatory input from the STN to the dopaminergic nuclei.

Mania can also be caused by physical injury or illness. Such a case of manic disorder is called secondary mania.

The mechanism underlying mania is unknown, but the neurocognitive profile of mania is largely consistent with dysfunction in the right prefrontal cortex, which is frequently seen in neuroimaging studies. Various lines of evidence from post-mortem studies and putative mechanisms of anti-manic agents point to abnormalities in GSK-3, dopamine, protein kinase C, and inositol monophosphatase (IMPase).

A meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies demonstrates increased thalamic activity and a bilateral decrease in activation of the inferior frontal gyrus. Activity in the amygdala and other subcortical structures such as the ventral striatum (the site of motivation and reward stimulus processing) is generally increased, although results are inconsistent and probably depend on task characteristics.

The decrease in functional connectivity between the ventral prefrontal cortex and the amygdala, along with variable data, supports the hypothesis of a general dysregulation of subcortical structures by the prefrontal cortex. A bias towards positive-valence stimuli and increased responsiveness in reward circuits may predispose to mania. And if mania is associated with damage to the right side of the hemisphere, then depression is usually associated with damage to the left hemisphere.

Manic episodes can be caused by dopamine receptor agonists. That said, combined with a preliminary report of increased VMAT2 activity as measured by radioligand binding PET scans, suggests a role for dopamine in mania. A decrease in the level of cerebrospinal fluid in the metabolite of serotonin 5-HIAA was also found in manic patients, which may be due to impaired serotonergic regulation and dopaminergic hyperactivity.

Limited evidence suggests that mania is associated with a behavioral "reward" theory. The electrophysiological evidence supporting this comes from studies linking left frontal EEG activity to mania. The left prefrontal region on the EEG may be a reflection of behavioral activity in the system of its activation. Evidence for neuroimaging during acute mania is sparse, but one study reported increased orbitofrontal cortex activity to monetary reward and another study reported increased striatal activity.

Classification and stages of development of manic disorder

In the ICD-10, there are several disorders for manic syndrome:

- organic manic disorder (F06.30);

- mania without psychotic symptoms (F30.1);

- mania with psychotic symptoms (F30.2);

- other manic episodes (F30.8);

- unspecified manic episode (F30.9);

- manic type of schizoaffective disorder (F25.0);

- manic affective disorder, current manic episode without psychotic symptoms (F31.1);

- manic affective disorder, current manic episode with psychotic symptoms (F31.2).

Mania can be divided into three stages. The first stage corresponds to hypomania, which is manifested by sociability and a feeling of euphoria. However, in the second (acute) and third (delusional) stages of mania, the patient's condition can become extremely irritable, psychotic, or even delusional. With simultaneous excitability and depression of a person, a mixed episode is observed.

In a mixed affective state, a person, although meeting the general criteria for a hypomanic or manic episode, experiences three or more concurrent depressive symptoms. This has led to some speculation among physicians that mania and depression, rather than representing "true" polar opposites, are rather two independent axes on a unipolar-bipolar spectrum.

Mixed affective state, especially with severe manic symptoms, increases the risk of suicide. Depression itself is a risk factor, but, combined with an increase in energy and purposeful activity, the patient is more likely to commit an act of violence on suicidal impulses.

Hypomania is a reduced state of mania that impairs function or quality of life to a lesser extent. It, in its essence, allows you to increase productivity and creativity. In hypomania, reduced need for sleep and goal-motivated behavior increase metabolism. While the increased mood and energy levels associated with hypomania can be seen as an advantage, mania itself tends to have many undesirable consequences, including suicidal tendencies. Hypomania may indicate.

A single manic episode is enough to diagnose a manic disorder in the absence of secondary causes (i.e. substance use disorder, pharmacological, general health).

Manic episodes are often complicated by delusions and/or hallucinations. If the psychotic features persist for a longer time than the episode of mania (two weeks or more), the diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder is more certain.

Some diseases from the spectrum of obsessive-compulsive disorders, as well as impulse control disorders, are called "mania", namely kleptomania, pyromania and trichotillomania. However, no relationship exists between mania or manic disorder with these disorders.

Hyperthyroidism can cause symptoms similar to mania, such as agitation, increased mood and energy, hyperactivity, sleep disturbances, and sometimes, especially in severe cases, psychosis.

Complications of manic disorder

If a manic disorder is left untreated, it can lead to more serious problems that affect the patient's life. These include:

- drug and alcohol abuse;

- rupture of social relations;

- poor performance at school or at work;

- financial or legal difficulties;

- suicidal behavior.

Diagnosis of manic disorder

Before starting treatment for mania, a thorough differential diagnosis should be made to rule out secondary causes.

There are several other psychiatric disorders with symptoms similar to those of a manic disorder. These disorders include, serious, (ADHD), as well as some personality disorders such as.

Although there are no biological tests that can diagnose manic disorder, blood tests and/or imaging may be done to rule out medical conditions with clinical manifestations similar to manic disorder.

Neurological diseases such as multiple sclerosis, complex partial seizures, strokes, brain tumors, Wilson's disease, traumatic brain injury, Huntington's disease and complex ones can mimic the features of a manic disorder.

Electroencephalography (EEG) can be used to rule out neurological disorders such as epilepsy, and computed tomography or MRI of the head can be used to rule out brain damage and endocrine disorders such as hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, and to differentiate from connective tissue diseases (systemic red lupus).

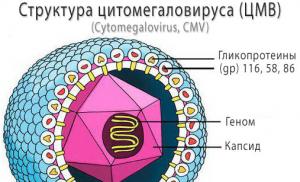

Infectious causes of mania that may appear similar to bipolar mania include herpes encephalitis, HIV, or neurosyphilis. Some vitamin deficiencies such as pellagra (niacin deficiency), vitamin B12 deficiency, folate deficiency, and Wernicke Korsakoff syndrome (thiamine deficiency) can also lead to mania.

Manic disorder treatment

Family-oriented therapy for manic disorder in adults and children begins with the assumption that negativity in the family environment (often a product of the stress and burden of caring for a sick relative) is a risk factor for subsequent manic episodes.

The therapy has three goals:

- increase the family's ability to recognize the escalation of early subsyndromal symptoms;

- reduce family interactions characterized by high criticism and hostility;

- increase the ability of the person at risk to cope with stress and adversity.

This is done through three healing modules:

- psychological education for the child and family about the nature, causes, course and treatment of manic disorder, as well as about self-management;

- strengthening communication learning to reduce negative communication and achieve the maximum protective effect of the family environment;

- problem-solving skills that can directly reduce the impact of specific family conflicts.

Psychological education It starts with introducing the family to goals and expectations. Family members are provided with a self-care guide (Miklowitz & George, 2007) that outlines the main symptoms of childhood mood disorder, risk factors, most effective treatments, and self-management tools. The purpose of the second session is to familiarize the family with the signs and symptoms of severe mood disorder, its subsyndromic and prodromal forms. This task is facilitated by a handout that distinguishes between “mood symptoms” and “usual mood” in two columns. The handout structures a discussion of how the at-risk child's mood differs and does not differ from what is normal for their age. The child is also encouraged to note changes in mood and sleep/wake patterns on a daily basis using a mood chart.

Family-centered treatment is one of the many options for early intervention. Other treatments may include interpersonal therapy to focus on managing social issues and regulating social and circadian rhythms, as well as individual or group cognitive behavioral therapy to teach adaptive thinking and emotional self-regulation skills.

Medical treatment manic disorder includes use as mood stabilizers (valproate, lithium, or carbamazepine) or atypical antipsychotics (olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, or aripiprazole). Although hypomanic episodes may only respond to a mood stabilizer, full blown episodes are treated with an atypical antipsychotic (often in combination with a mood stabilizer as they tend to produce the most rapid improvement).

Once the manic behavior has disappeared, long-term treatment focuses on preventive treatment to try to stabilize the patient's mood, usually through a combination of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. The chance of relapse is very high for those who have experienced two or more episodes of mania or depression. While treating manic disorder is important for treating symptoms of mania and depression, studies show that relying on medication alone is not the most effective treatment. The drug is most effective in combination with psychotherapy, self-help, coping strategies and a healthy lifestyle.

Lithium is a classic mood stabilizer for preventing further manic symptoms. A systematic review found that long-term lithium treatment reduced the risk of manic relapse by 42%. Anticonvulsants such as valproate, oxcarbazepine, and carbamazepine are also used for prevention. Clonazepam (Klonopin) is also used. Sometimes atypical neuroleptics are used in combination with the previously mentioned drugs, including olanzapine (Zyprexa), which helps treat hallucinations or delusions, Asenapine (prescription, Sycrest), aripiprazole (Abilify), risperidone, ziprasidone, and clozapine, which is often assigned to people. who do not respond to lithium or anticonvulsants.

Verapamil, a calcium channel blocker, is useful in the treatment of hypomania and in cases where lithium and mood stabilizers are contraindicated or ineffective. Verapamil is effective for both short-term and long-term treatment.

Antidepressant monotherapy is not recommended for the treatment of depression in patients with type I or type II manic disorder. The combination of antidepressants with mood stabilizers did not have the desired positive effect on these patients.

Forecast. Prevention

As mentioned earlier, the risk of manic disorder is genetically mediated, and can often be observed as subsyndromic signs of the disease. In addition, interpersonal and familial stress associated with the development of symptoms (both symptom-induced stress and uncontrollable stressors or adversity that prevent a child from successfully adapting to development) can interfere with prefrontal-mediated mood regulation. In turn, poor emotional self-regulation may be associated with increased cyclicity and resistance to pharmacological interventions. Thus, preventive interventions (i.e., those given prior to the first fully syndromic manic episode) that alleviate early symptoms, increase the ability to cope with dependent and independent stressors, and restore healthy prefrontal neural circuitry should reduce the likelihood of adverse outcomes of the disorder (Chang et al. 2006,). With these assumptions, the intervention planning researcher or clinician can intervene at the level of biological markers (eg, brain-derived neurotrophic growth factor), environmental stressors (eg, aversion to family interactions), subsyndromic mood, or ADHD symptoms.

It can be argued that the treatment of a child at risk should begin with psychotherapy and progress to pharmacotherapy only if the child continues to be unstable or worsens. Although psychotherapy requires more time and effort than psychopharmacology, it can be a precise, targeted intervention with lasting effects even after it is completed (Vittengl, Clark, Dunn, & Jarrett, 2007).

Psychotherapy does not usually cause potentially harmful side effects. In contrast, medications such as the atypical antipsychotic olanzapine (often used as a mood stabilizer), while reducing conversion rates to psychosis among at-risk adolescents, may be associated with significant weight gain and “metabolic syndrome” (McGlashan et al. 2006 ).

Medications are likely to have little effect on the intensity of external stressors and will not buffer the person at risk from stress once they stop taking them. In contrast, psychosocial interventions can reduce psychosocial vulnerabilities and increase the resilience and coping of those at risk. Involving the family in treatment can also help the caring parent recognize how their own vulnerabilities, such as an individual's history of mood disorder, translate into hostile parent/offspring interactions that can promote offspring responsibility.

Despite important advances, relatively little is known about the actual constellation of risk and protective factors that most accurately predict the onset of manic disorder or weigh genetic, neurobiological, social, familial, or cultural factors at different developmental stages. It can be argued that the clarification of these developmental trajectories is a necessary precondition for fully effective preventive interventions, especially if therapeutic targets can be identified at various stages of development. Research examining the interaction of genetic, neurobiological, and environmental factors should be useful in identifying these intervention targets.

We have long known that differences in social environments can lead to differences in gene expression and variations in brain structure or function, and recursively, variations in genetic vulnerability or brain function can lead to differential environmental selection. The puzzle is how best to explore the role of environmental variables while controlling for the role of genetic factors, and vice versa. Studying the role of the environment in married couples or identical twins can help control the role of shared environmental factors and allow the study of the role of undivided familial or other environmental factors. For an example of antisocial behavior, Caspi et al. (2004) showed that among identical twin pairs, the twin to whom the mother expressed more emotional negativity and less warmth was at greater risk of developing antisocial behavior than the twin to whom the mother expressed less negativity and more warmth. Similar experimental designs can be usefully applied to siblings or paired twins who have manic disorder to clarify how different stressors lead to differences in gene expression and the likelihood of developing mood episodes.

Understanding these diverse developmental pathways will help us tailor our early intervention and prevention efforts, which may mean designing different interventions for children with different prodromal presentations. For prodromal children with the highest genetic burdens for mood disorder, early intervention with medication can have a huge impact on later outcomes. In contrast, young people for whom environmental contextual factors play a central role in triggering episodes (for example, adolescent girls with a history of sexual abuse and current family conflict) may benefit most from interventions that focus on enhancing the protective effects of immediate social environment, with pharmacotherapy introduced only as a rescue strategy.

Finally, the results of research, preventive measures can shed light on the nature of genetic, biological, social and cultural mechanisms. Indeed, if early intervention trials show that changing familial interactions reduces the risk of early bipolar disorder, we will have evidence that familial processes play a causative rather than reactive role in some of the trajectories of manic disorder. In parallel, if treatment-related changes in neurobiological risk markers (such as amygdala volume) improve the trajectory of early mood symptoms or comorbidities, we can develop hypotheses for these biological risk markers. The next generation of research into the development of manic disorder should address these questions.

All sub-categories of this three-digit category must be used for a single episode only. Hypomanic or manic episodes in cases where one or more affective episodes (depressive, hypomanic, manic or mixed) have occurred in the past should be coded as bipolar affective disorder (F31.-)

Includes: bipolar disorder, single manic episode

Hypomania

A disorder characterized by a persistent elevation of mood, increased energy and activity, and usually a marked sense of well-being and mental and physical productivity. Increased sociability, talkativeness, overfamiliarity, increased sexuality, and reduced need for sleep often occur, but not to the point of severe impairment and social exclusion. Irritability, self-importance, rudeness can replace the more usual euphoric relationships. Mood and behavioral disturbances are not accompanied by hallucinations or delusions.

Mania without psychotic symptoms

The mood is elevated without regard to the real circumstances of the patient's life and can vary from carefree gaiety to almost uncontrollable excitement. Elevated mood is accompanied by an increase in energy, developing into hyperactivity and talkativeness, and a decrease in the need for sleep. Expressed inability to concentrate, often there is a significant absent-mindedness. Feelings of self-esteem often become pompous with grandiose ideas and overconfidence. The loss of normal social restraint entails behavior characterized by recklessness, riskiness, inappropriateness and inconsistency with the character of the patient.

Mania with psychotic symptoms

In addition to the clinical picture described in subheading F30.1, there is delusions (usually grandiose) or hallucinations (usually voices addressing the patient directly) or agitation, excessive motor activity, and flashes of ideas so pronounced that the individual becomes inaccessible to normal communication .

To date, three degrees of severity of manic disorders are conventionally distinguished:

Causes

Why this disorder occurs has not been clarified, at least to date. According to most psychiatrists and neurologists, genetic factors play a huge role in causing a manic episode.

But it is also not excluded that the environment, psychosocial factors, neuroendocrine disorders can also influence.

Symptoms of a manic episode

How to identify a manic episode? Signs may be as follows:

- Increased self-esteem;

- A person practically does not need sleep;

- Talkativeness;

- Thought jumps;

- Inattention, easy distractibility;

- Social, sexual activity.

Diagnosis of the disease

Treatment of a manic episode begins with a diagnosis of the disorder. First of all, this is a clinical method, that is, interviewing the patient, observing behavior.

In the course of communication not only with the patient, but also with relatives, the doctor tries to find out whether the relatives had such disorders (that is, confirms or excludes the genetic factor). The doctor also finds out the patient's personality, asks about the features of his development, family and social status, how he reacts to various stressful situations. Also important is the fact whether the patient had mental trauma.

If it is still necessary to conduct studies to confirm or refute the diagnosis, then

manic episode is an affective disorder characterized by a pathologically elevated background of mood and an increase in the volume and pace of physical and mental activity.

The patient's mood is elevated inappropriately for the circumstances and can vary from carefree gaiety to almost uncontrollable excitement. The rise in mood is accompanied by increased energy, leading to hyperactivity, excessive volume and speed of speech production, an increase in vital drives (appetite, sexual desire), and a decrease in the need for sleep. Perceptual disturbances may occur. Normal social inhibition is lost, attention is not retained, pronounced distractibility is noted, overestimated self-esteem, over-optimistic ideas and ideas of greatness are easily expressed. The patient has many plans, but none of them is fully realized. Criticism is reduced or absent. The patient loses the ability to critically assess their own problems; possible inappropriate actions with negative consequences for social status and material well-being, may commit extravagant and impractical acts, spend money thoughtlessly or be aggressive, amorous, hypersexual, playful in inappropriate circumstances.

In some manic episodes, the patient's condition can be characterized as irritable and suspicious, rather than elated. Mania with psychotic symptoms is experienced by 86% of patients with bipolar disorder during their lifetime. At the same time, increased self-esteem and ideas of superiority turn into delusional ideas of greatness, irritability and suspicion transform into delusions of persecution. In severe cases, there may be expansive-paraphrenic feelings of grandeur or delusional ideas about noble birth. As a result of the jump of thoughts and verbal pressure, the patient's speech often turns out to be incomprehensible to others.

Manic episodes are much less common than depression: according to various sources, their prevalence is 0.5-1%. Separately, it should be noted that a manic episode in cases where one or more affective episodes (depressive, manic or mixed) have already occurred in the past is diagnosed as part of a bipolar affective disorder and is not considered independently.

Today, three degrees of severity of manic disorders are conventionally distinguished:

- Hypomania

Hypomania- This is a mild degree of mania. There is a constant slight rise in mood (at least for a few days), increased energy and activity, a sense of well-being and physical and mental productivity. Increased sociability, talkativeness, excessive familiarity, increased sexual activity, and decreased need for sleep are also common. However, they do not lead to serious violations in the work or social rejection of patients. Instead of the usual euphoric sociability, irritability, heightened self-importance, and rude behavior may be observed.

Concentration and attention can be disturbed, thus reducing opportunities for both work and leisure. However, this state does not prevent the emergence of new interests and activity or a moderate propensity to spend.

Mania without psychotic symptoms- This is a moderate degree of mania. The mood is elevated inappropriately for the circumstances and can vary from careless gaiety to almost uncontrollable excitement. The elevation of mood is accompanied by increased energy, leading to hyperactivity, speech pressure, and reduced need for sleep. Normal social inhibition is lost, attention is not retained, marked distractibility, increased self-esteem, over-optimistic ideas and ideas of greatness are easily expressed.

Perceptual disturbances may occur, such as the experience of a color as particularly bright (and usually beautiful), a preoccupation with fine details of some surface or texture, and subjective hyperacusis. The patient may take extravagant and impractical steps, spend money recklessly, or become aggressive, amorous, playful in inappropriate circumstances. In some manic episodes, the mood is more irritable and suspicious than elated. The first attack often occurs at the age of 15-30 years, but can be at any age from childhood to 70-80 years.

Mania with psychotic symptoms- this is a severe degree of mania. The clinical picture corresponds to a more severe form than mania without psychotic symptoms. Heightened self-esteem and grandiosity may develop into delusions, and irritability and suspicion may develop into delusions of persecution. In severe cases, pronounced delusions of grandeur or noble birth are noted. As a result of the jump of thoughts and speech pressure, the patient's speech becomes incomprehensible. Severe and prolonged physical activity and arousal can lead to aggression or violence. Neglect of food, drink, and personal hygiene can lead to a dangerous state of dehydration and neglect. Delusions and hallucinations may be classified as mood-appropriate or not.

Manic episodes, if untreated, have a duration of 3-6 months with a high probability of relapse (manic episodes recur in 45% of cases). Approximately 80-90% of patients with manic syndromes develop a depressive episode over time. With timely treatment, the prognosis is quite favorable: 15% of patients recover, 50-60% recover incompletely (numerous relapses with good adaptation in the intervals between episodes), in a third of patients there is a possibility of the disease becoming chronic with persistent social and labor maladaptation.

What Triggers/Causes of a Manic Episode:

The etiology of the disorder has not yet been fully elucidated. According to most neurologists and psychiatrists, genetic factors play the most important role in the onset of the disease, this assumption is supported by the high frequency of the disorder in the families of patients, an increase in the likelihood of developing the disease with increasing degree of relationship, as well as a 75% level of the probability of developing the disease in monozygotic twins. However, the provocative influence of environmental changes is not excluded. Among the possible etiological factors, there are: metabolic disorders of biogenic amines (serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine), neuroendocrine disorders, sleep disorders (reduction in duration, frequent awakenings, sleep-wake rhythm disturbance), and even psychosocial factors.

Pathogenesis (what happens?) during a manic episode:

Symptoms of a manic episode:

Criteria for a manic episode:

- inflated self-esteem a sense of self-importance or grandiosity;

- reduced need for sleep;

- increased talkativeness, obsession in conversation;

- jumps of thoughts, a feeling of "flight of thought";

- instability of attention;

- increased social, sexual activity, psychomotor excitability;

- involvement in risky transactions with securities, thoughtlessly large expenses, etc.

A manic episode may include delusions and hallucinations, including

A diagnosis of mania requires at least three of the symptoms listed, or four if one of the symptoms is irritability, and the duration of the episode must be at least 2 weeks, but the diagnosis may be made for shorter periods if the symptoms are unusually severe. and they come fast.

Diagnosis of a manic episode:

In the diagnosis of a manic episode, the main method is the clinical method. In it, the main place belongs to the questioning (clinical interview) and objective observation of the patient's behavior. With the help of questioning, a subjective anamnesis is collected and clinical facts are revealed that determine the mental state of the patient.

An objective history is collected by studying medical records, as well as from conversations with the patient's relatives.

The purpose of taking anamnesis is to obtain data on:

- hereditary burden of mental illness;

- the patient's personality, features of his development, family and social status, transferred exogenous hazards, features of response to various everyday situations, mental trauma;

- characteristics of the mental state of the patient.

When taking a history of a patient with a manic episode, attention should be paid to the presence of risk factors such as:

- episodes of affective disorders in the past;

- affective disorders in a family history;

- history of suicidal attempts;

- chronic somatic diseases;

- stressful changes in life circumstances;

- alcoholism or drug addiction.

Additional examination methods include clinical and biochemical blood tests (including glucose, ALT, AST, alkaline phosphatase; thymol test);

Manic episode treatment:

Treatment for a manic state is usually inpatient, the length of stay in the hospital depends on the rate of reduction of symptoms (average 2-3 months). Post-treatment is possible in semi-stationary or outpatient conditions.

There are three relatively independent stages in the system of therapeutic measures:

- cupping therapy aimed at treating the current condition;

- aftercare or stabilizing (maintenance) therapy aimed at preventing exacerbation of the previous condition;

- prophylactic therapy aimed at preventing relapse (repeated condition).

At the stage of cupping therapy, the drugs of choice are lithium salts (lithium carbonate, lithium oxybate), carbamazepine, salts of valproic acid (sodium valproate).

In case of sleep disturbance, hypnotics (hypnotics) are added - nitrazepam, flunitrazepam, temazepam, etc.

With severe psychomotor agitation, aggressiveness, and the presence of manic-delusional symptoms, antipsychotics are prescribed (usually haloperidol, which is administered parenterally if necessary), the dose of which, as the therapeutic effect is achieved, is gradually reduced until it is completely canceled. For the rapid reduction of psychomotor agitation, zuclopenthixol is used. The use of antipsychotics is necessary due to the fact that the effect of normotimics appears only after 7-10 days of treatment. With motor agitation and sleep disorders, antipsychotics with a sedative effect are used (chlorpromazine, levomepromazine, thioridazine, chlorprothixene, etc.).

If there is no effect in the first month of treatment, a transition to intensive care is necessary: alternating high doses of incisive antipsychotics with sedatives, adding parenterally administered anxiolytics (phenazepam, lorazepam). In cases of resistant mania, combination therapy with lithium salts and carbamazepine, lithium salts and clonazepam, lithium salts and valproic acid salts is possible.

At the second stage, the use of lithium salts should last an average of 4-6 months to prevent an exacerbation of the condition. Lithium carbonate or its prolonged forms are used; the concentration of lithium in plasma is maintained within the range of 0.5-0.8 mmol / l. The issue of discontinuing therapy with lithium preparations is decided depending on the characteristics of the course of the disease and the need for preventive therapy.

The minimum duration of maintenance therapy is 6 months after the onset of remission. When therapy is discontinued, it is considered advisable to slowly reduce the dose of the drug for at least 4 weeks.

Prevention of a manic episode:

Which Doctors Should You See If You Have a Manic Episode:

Are you worried about something? Do you want to know more detailed information about the Manic episode, its causes, symptoms, methods of treatment and prevention, the course of the disease and diet after it? Or do you need an inspection? You can book an appointment with a doctor– clinic Eurolaboratory always at your service! The best doctors will examine you, study the external signs and help identify the disease by symptoms, advise you and provide the necessary assistance and make a diagnosis. you also can call a doctor at home. Clinic Eurolaboratory open for you around the clock.

How to contact the clinic:

Phone of our clinic in Kiev: (+38 044) 206-20-00 (multichannel). The secretary of the clinic will select a convenient day and hour for you to visit the doctor. Our coordinates and directions are indicated. Look in more detail about all the services of the clinic on her.

(+38 044) 206-20-00

If you have previously performed any research, be sure to take their results to a consultation with a doctor. If the studies have not been completed, we will do everything necessary in our clinic or with our colleagues in other clinics.

You? You need to be very careful about your overall health. People don't pay enough attention disease symptoms and do not realize that these diseases can be life-threatening. There are many diseases that at first do not manifest themselves in our body, but in the end it turns out that, unfortunately, it is too late to treat them. Each disease has its own specific signs, characteristic external manifestations - the so-called disease symptoms. Identifying symptoms is the first step in diagnosing diseases in general. To do this, you just need to several times a year be examined by a doctor not only to prevent a terrible disease, but also to maintain a healthy spirit in the body and the body as a whole.

If you want to ask a doctor a question, use the online consultation section, perhaps you will find answers to your questions there and read self care tips. If you are interested in reviews about clinics and doctors, try to find the information you need in the section. Also register on the medical portal Eurolaboratory to be constantly up to date with the latest news and information updates on the site, which will be automatically sent to you by mail.

Other diseases from the group Mental and behavioral disorders:

| Agoraphobia |

| Agoraphobia (fear of empty spaces) |

| Anancaste (obsessive-compulsive) personality disorder |

| Anorexia nervous |

| Asthenic disorder (asthenia) |

| affective disorder |

| affective mood disorders |

| Insomnia of an inorganic nature |

| bipolar affective disorder |

| bipolar affective disorder |

| Alzheimer's disease |

| delusional disorder |

| delusional disorder |

| bulimia nervosa |

| Vaginismus of inorganic nature |

| voyeurism |

| generalized anxiety disorder |

| Hyperkinetic disorders |

| Hypersomnia of inorganic nature |

| Hypomania |

| Motor and volitional disorders |

| Delirium |

| Delirium not due to alcohol or other psychoactive substances |

| Dementia in Alzheimer's disease |

| Dementia in Huntington's disease |

| Dementia in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease |

| Dementia in Parkinson's disease |

| Dementia in Pick's disease |

| Dementia in diseases caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) |

| Depressive disorder recurrent |

| depressive episode |

| depressive episode |

| Childhood autism |

| Antisocial personality disorder |

| Dyspareunia of inorganic nature |

| dissociative amnesia |

| dissociative amnesia |

| Dissociative anesthesia |

| dissociative fugue |

| dissociative fugue |

| dissociative disorder |

| Dissociative (conversion) disorders |

| Dissociative (conversion) disorders |

| Dissociative movement disorders |

| Dissociative motor disorders |

| Dissociative seizures |

| Dissociative seizures |

| dissociative stupor |

| dissociative stupor |

| Dysthymia (depressed mood) |

| Dysthymia (low mood) |

| Other organic personality disorders |

| dependent personality disorder |

| Stuttering |

| induced delusional disorder |

| hypochondriacal disorder |

| Histrionic Personality Disorder |

| catatonic syndrome |

| Catatonic disorder of an organic nature |

| nightmares |

| mild depressive episode |

| Mild cognitive impairment |

| Mania without psychotic symptoms |

| Mania with psychotic symptoms |

| Violation of activity and attention |

| Developmental disorder |

| Neurasthenia |

| Undifferentiated somatoform disorder |

| Non-organic encopresis |

| Nonorganic enuresis |

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder |

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder |

| Orgasmic dysfunction |

| Organic (affective) mood disorders |

| organic amnestic syndrome |

| organic hallucinosis |

| Organic delusional (schizophrenia-like) disorder |

| organic dissociative disorder |

| organic personality disorder |

| Organic emotionally labile (asthenic) disorder |

| Acute reaction to stress |

| Acute reaction to stress |

| Acute polymorphic psychotic disorder |

| Acute polymorphic psychotic disorder with symptoms of schizophrenia |

| Acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder |

| Acute and transient psychotic disorders |

| No genital response |

| Lack or loss of sex drive |

| panic disorder |

| panic disorder |

| paranoid personality disorder |

| Pathological addiction to gambling (mania) |

| Pathological arson (pyromania) |

| Pathological theft (kleptomania) |

| Pedophilia |

| Increased sex drive |

| Eating inedible (pika) in infancy and childhood |

| postconcussion syndrome |

| PTSD |

| Post Traumatic Stress Disorder |

| Postencephalitic syndrome |

| premature ejaculation |

| Acquired aphasia with epilepsy (Landau-Kleffner syndrome) |

| Mental and behavioral disorders due to alcohol use |

| Mental and behavioral disorders due to the use of hallucinogens |

| Mental and behavioral disorders due to the use of cannabinoids |

| Mental and behavioral disorders due to cocaine use |

| Mental and behavioral disorders due to caffeine use |

| Mental and behavioral disorders due to the use of volatile solvents |

| Mental and behavioral disorders due to opioid use |

| Mental and behavioral disorders due to the use of psychoactive substances |

| Mental and behavioral disorders due to the use of sedatives and hypnotics |

| Mental and behavioral disorders due to tobacco use |

| Mental and behavioral disorders associated with the postpartum period |

| Intellectual Disorders |

| Conduct disorders |

| Gender Identification Disorders in Children |

| Disorders of habits and drives |

| Disorders of sexual preference |

| Sleep disorders of inorganic nature |

| Disorders of emotion and affect |

| Disorder of perception and imagination |

| Personality disorder |

| Multiple Personality Disorder |

| thought disorder |

| Memory and attention disorder |

| Eating disorders in infancy and childhood |

| puberty disorder |

Manic episode See synonym: .

Brief explanatory psychological and psychiatric dictionary. Ed. igisheva. 2008 .

See what "Manic episode" is in other dictionaries:

manic episode- a current attack of mania or such an attack in the anamnesis ... Encyclopedic Dictionary of Psychology and Pedagogy

MANIC EPISODE- A distinct period during which the predominant mood is mania (2) ... Explanatory Dictionary of Psychology

"F30" Manic Episode- Three degrees of severity are distinguished here, in which there are common characteristics of increased mood and an increase in the volume and pace of physical and mental activity. All subheadings of this category should be used only for a single ... ...

F30.9 Manic episode, unspecified- Turns on: Mania NOS... Classification of mental disorders ICD-10. Clinical descriptions and diagnostic instructions. Research Diagnostic Criteria

episode- n., m., use. comp. often Morphology: (no) what? episodes for what? episode, (see) what? episode what? episode about what? about the episode pl. what? episodes of what? episodes for what? episodes, (see) what? episodes of what? episodes about what? about episodes 1.… … Dictionary of Dmitriev

A mental disorder characterized by a state of high spirits or excitement, not arising from the circumstances of life and ranging from increased vitality (hypomania) to violent, almost uncontrollable excitement ... Great Psychological Encyclopedia

F31.5 Bipolar affective disorder, current episode of severe depression with psychotic symptoms.- A. Current episode meeting the criterion for major depressive episode with psychotic symptoms (F32.3). B. Past at least one well-described hypomanic or manic episode (F30.) or mixed affective episode ... ... Classification of mental disorders ICD-10. Clinical descriptions and diagnostic instructions. Research Diagnostic Criteria

F31.6 Bipolar affective disorder, current episode mixed- The patient must have had at least one manic, hypomanic, depressive or mixed affective episode in the past. In the present episode, either mixed or rapidly alternating manic, hypomanic or ... ... Classification of mental disorders ICD-10. Clinical descriptions and diagnostic instructions. Research Diagnostic Criteria

"F31.3" Bipolar affective disorder, current episode of mild or moderate depression- Diagnostic guidelines: For a definite diagnosis: a) the current episode must meet the criteria for a depressive episode of either mild (F32.0x) or moderate severity (F32.1x). b) there must have been at least one hypomanic in the past, ... ... Classification of mental disorders ICD-10. Clinical descriptions and diagnostic instructions. Research Diagnostic Criteria

"F31.5" Bipolar affective disorder, current episode of severe depression with psychotic symptoms- Diagnostic guidelines: For a definite diagnosis: a) the current episode meets the criteria for major depressive episode with psychotic symptoms (F32.3x); b) there must have been at least one hypomanic, manic or ... ... Classification of mental disorders ICD-10. Clinical descriptions and diagnostic instructions. Research Diagnostic Criteria